July 3, 2000

UCSC computer scientists analyze and assemble data for Human Genome Project

By Tim Stephens

In an intensive effort over the past few months, UCSC researchers created a powerful

new computer program and used it to assemble the "working draft" of the

human genome announced last week by leaders of the international Human

Genome Project.

|

| David Haussler, director of the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering,

was recruited to work on the Human Genome Project early this year. Photo: UCSC Photo Services |

|

| Graduate student Jim Kent in the garage office where he wrote most of the software

code used to assemble the working draft of the human genome sequence. Photo: Don Harris |

|

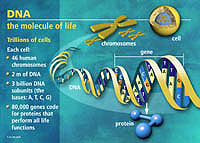

| UCSC researchers helped assemble a working draft of the complete sequence of 3

billion letters of DNA code in the human genome (view larger

image). Graphic: DOE Human Genome Program |

At a press conference in Washington, D.C., Francis Collins, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health, and other leaders of the Human Genome Project public consortium announced that the consortium has completed a working draft of the sequence of the human genome--the genetic blueprint for a human being.

The public release of this working draft is a landmark achievement, although much work remains to be done. The Human Genome Project involves a public consortium of more than 1,000 scientists at institutions in the United States and Europe. David Haussler, professor of computer science and director of the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering at UCSC, joined the project early this year. Haussler has been working closely with Eric Lander, director of the Genome Center at MIT's Whitehead Institute, who is directing the computational analysis of the human genome data.

"The analysis performed by Haussler's group at UC Santa Cruz was a crucial contribution to generating this working draft of the human genome sequence," Lander said.

Five laboratories, including Lander's group, have produced most of the raw data, determining the sequences of chemical building blocks that make up the DNA in human chromosomes.

The human genetic code is spelled out in roughly 3 billion DNA subunits, called

bases, arranged in specific sequences on the chromosomes. To determine those sequences,

Genome Project scientists divided the chromosomal DNA into about 25,000 small overlapping

regions for analysis by automated sequencing machines.

The sequencing procedures yielded sequences for many random fragments of DNA from

each region, providing a total of about 400,000 sequenced fragments of human DNA.

Having obtained the sequences of these random fragments, however, the researchers

faced a major challenge in trying to reassemble them to represent the sequences of

each of the 23 human chromosomes as accurately as possible.

"The computational analysis we performed was to try to determine the proper

order and orientation of each piece and to join overlapping pieces of the sequence

together," Haussler said.

Jim Kent, a graduate student in biology at UCSC who has a background in computer

science, designed and wrote most of the software used to perform the analysis, and

he did it in a remarkably short time frame. "He has done a phenomenal job of

creating the software to do this very complex operation," Haussler said.

The working draft generated by this analysis incorporates all of the sequence data

available as of June 15. It covers 85 percent of the genome and is 99.9 percent accurate.

The researchers will continue to fill in the remaining gaps and improve the order

and orientation of the fragments as more sequence data becomes available. They will

also begin analyzing the working draft to locate the genes buried within the genome

sequence.

The ultimate goal of the Human Genome Project is to identify and understand the function

of all of the genes contained within the human genome. This information will be a

boon to biomedical researchers, helping them to identify genes related to specific

diseases, to understand how genetic variations affect susceptibility to diseases

and responses to drugs, and to design new drugs. Of the human diseases known to be

linked to specific genes, 95 percent are associated with genes that have already

been located in the working draft of the genome.

"We are going through a portal, opening a door to a new world," Haussler

said. "When I saw the fragments from Jim Kent's first assembly of the genome

come flying across my computer screen, I thought, 'This is it...this is our genome.'

It is hard to describe the sense of wonder I felt."

The milestone comes 15 years after the idea of mapping the human genome was first

discussed at a historic meeting at UCSC in May 1985. Molecular biologist Robert L.

Sinsheimer, then Chancellor of UCSC, brought together about 20 leading biologists

from Europe and the United States to discuss the feasibility of such a project. The

U.S. Human Genome Project was formally launched in 1990.

In addition to Kent, Haussler's team at UCSC includes Nick Littlestone, a visiting

scientist at the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering; Scott Kennedy,

a graduate student in mathematics; Patrick Gavin, who just graduated from UCSC with

a B.S. in computer science; and systems consultant Paul Tatarsky.

Haussler expects to perform a new analysis soon incorporating all of the additional

sequence data available since June 15. He and his collaborators will be trying to

get a handle on how many genes there are, where they are located, what their structures

are, and what their functions might be.

"The analysis of the genes is the most challenging part of this whole undertaking,

and it is also the most interesting because that is where the potential lies for

making major discoveries," Haussler said.