January 8, 2007

Alumna's new book puts an international face on feminism

By Jennifer McNulty

Sasha Su-Ling Welland's new book tells the stories of her grandmother and great aunt, spirited and competitive sisters who came of age in China in the 1920s.

Sasha Su-Ling Welland documented her family history while she was a graduate student at UCSC. Photo: Jennifer McNulty |

|

As part of an international wave of "modern girls," these young women flouted convention as successfully as their Western counterparts, the familiar "flappers" of the Roaring '20s, and their lives reveal the international roots of feminism, says Welland (Ph.D. anthropology, '06).

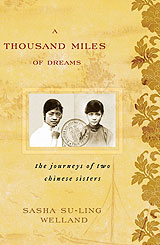

"The common story in the U.S. is that feminism started in the West and spread to the rest of the world, but it's a lot more complicated than that--and therefore more heartening," said Welland, author of A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters.

In the course of researching and writing the book, Welland also uncovered some "family secrets" that her grandmother had left out of her version of history, including the fact that Welland's great aunt became a famous writer in China.

"My grandmother studied science and medicine, while my great aunt pursued literature. Their choices reflected what was going on in China at the time," said Welland, an assistant professor of anthropology and women's studies at the University of Washington in Seattle, referring to widespread debate about what would save the nation from colonial encroachment--science or culture. "The paths they followed straddled either side of this debate. I think my grandmother was also jealous that her sister achieved the fame that she did, because my grandmother was very ambitious, too."

As a college student, Welland first heard and became enthralled by her grandmother's tales of growing up in China and emigrating to the United States to attend college. Her grandmother, Ling Shuhao, arrived in Cleveland in 1925 to study medicine in the midst of a U.S. crackdown on Chinese immigrant communities.

"She was feisty, and she fought hard," said Welland. "My grandmother was always the hero, the protagonist of her own stories."

But Shuhao's life in the United States was marked by "repeated compromise" and assimilation. As one of only two Chinese families in Indianapolis, Shuhao--"Amy" in her adopted country--and her husband succeeded as pharmacological researchers but also sought to fit in. "Amy pressured my mother to conform to dominant gender norms of 1950s America," said Welland. "In an ironic twist of fate, my grandmother pushed on her daughter everything she once ran away from as she pursued her own dream of independence."

By contrast, Shuhao's sister Ling Shuhua became a literary phenomenon in Beijing, authoring several books of short stories and essays. She was part of a prominent group of cosmopolitan Chinese intellectuals, had an affair with Virginia Woolf's nephew that drew her into the orbit of the Blooomsbury group, and spent much of her adult life in England.

Welland didn't learn of her great aunt's fame until she began documenting her grandmother's life as an undergraduate honors project at Stanford University. She delved more deeply into the project as a graduate student at UCSC, pursuing the project while writing her dissertation about the contemporary art world in Beijing.

"I thought I was almost done with the book when I started graduate school, but then I learned so much more from my professors," said Welland, singling out history professor Gail Hershatter's "nuanced study of women in China" as a major inspiration, as well as the scholarly mentorship of feminist studies professor Emily Honig, and anthropology professors Nancy Chen, Lisa Rofel, and Anna Tsing.

The project required extensive archival research, and Welland felt at times like a detective as she traveled to China and England to gather materials, conduct interviews, and meet relatives. She found letters, read copies of the original publications in which her great aunt's stories appeared, and collected old photos. The process brought history to life in an intimate way, she recalled.

"My grandmother and great aunt were caught in a transitional moment in China," she said. The daughters of an imperial scholar-official and a concubine, the sisters came of age during a period of enormous social, political, and economic change in China. As "modern girls," they cut their hair short, played sports, and demanded education and independence. "Chinese women in the 1920s were very cognizant of what was going on in the West, and vice versa," she said. "Feminism has always been a deeply international movement."

It's a chapter of Chinese history that is little known in the United States, said Welland. "You realize what's been erased and see how family omissions correlate with silences in the national history," she said, referring to the research as "a reeducation in 20th-century history on both sides of the Pacific."

Welland's great aunt's fiction mostly depicted older-style families and relatively elite women, but as part of the ongoing literary revolution of the era, Ling Shuhua wrote in vernacular, not classical, Chinese. "She wrote the way people spoke," said Welland. "She wrote about disintegrating families, and although her writing was criticized by some as not revolutionary enough, I think her more subtle intent was to expose the tensions, jealousies, and difficulties women experienced within that type of family system."

The two sisters, motivated by a similar desire to overturn tradition, told versions of their family history that diverged in characteristic ways, said Welland. Ling Shuhua eventually published an English-language memoir entitled Ancient Melodies, in which she detailed the power struggles between her father's six wives. "Amy, by contrast, edited her family tree to include one father and one mother, the typical American nuclear family," said Welland.

Today, Welland calls her grandmother's oversights "errors of emotional omission" and is fascinated by how family histories "articulate with history writ large." As a mixed-race Asian American from Missouri, Welland hungered to hear her grandmother's stories because they shattered the predominant popular images of passive, permissive Asian women.

In her book, Welland seeks to show how her grandmother and great aunt "crafted their stories to fit who they wanted to become," and she provides the social context that illuminates their choices. Writing the book didn't necessarily feel like reconciliation, however.

"To tell the two sisters' stories together is to betray both of them," Welland said with a resigned smile.

View a book reading by Welland at Books Inc. in San Francisco on December 7.

Welland also participated in a panel discussion on "Family Secrets, Family Truths: American Immigrant Stories" at the Miami Book Fair International on November 18. A downloadable audio recording is available through Beyond the Book, a podcast series produced by the Copyright Clearance Center.

Profiles of other UCSC alumni are available online.