November 14, 2005

Rapidly accelerating glaciers may increase how fast the sea level rises

By Emily Saarman

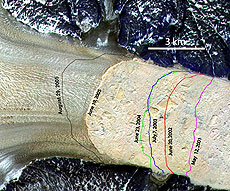

Satellite images show that, after decades of stability, a major glacier draining the Greenland ice sheet has dramatically increased its speed and retreated nearly five miles in recent years.

Lines

on this satellite image of Greenland's Helheim glacier show

the positions of the glacier front between 2001 and 2005.

Image: I. Howat et al. Lines

on this satellite image of Greenland's Helheim glacier show

the positions of the glacier front between 2001 and 2005.

Image: I. Howat et al. |

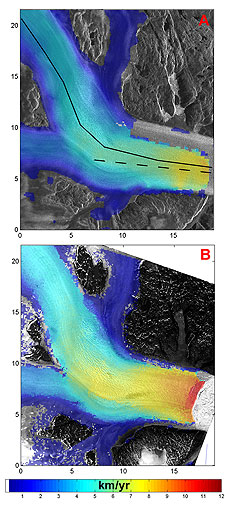

Colors corresponding to the rate of flow show the increase in ice flow velocity on the Helheim glacier between 2001 and 2005. Colors corresponding to the rate of flow show the increase in ice flow velocity on the Helheim glacier between 2001 and 2005.

Images:

Howat et al

|

These changes could contribute to rapid melting of the Greenland ice sheet and cause the global sea level to rise faster than expected, according to researchers studying the glacier.

A paper describing these findings will be published this month in Geophysical Research Letters. The study focused on the Helheim glacier, one of the largest outlet glaciers in Greenland. Warming air and sea temperatures in the area likely caused the glacier to speed up, said Slawek Tulaczyk, associate professor of Earth sciences and a coauthor of the paper.

The Greenland ice sheet contains enough water to raise global sea levels by 15 to 20 feet. Although the entire ice sheet is unlikely to melt in this century, even a small change in the rate of melting could inundate low-lying coastal plains and add enough fresh water to the North Atlantic to change ocean circulation patterns, Tulaczyk said.

Ian Howat, a doctoral candidate in Earth sciences and first author on the paper, said changes such as this could have dramatic implications for climate models. Scientists use complex mathematical models to predict how climate, sea level, and ocean circulation will change in response to growing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

"Current models treat the ice sheet like it's just an ice cube sitting up there melting, and we're finding it's not that simple," Howat said.

The researchers used satellite images to determine the movement and retreat of Helheim glacier. Howat tracked the positions of glacial surface features to assess how fast the glacier moved between satellite fly-bys. Satellite images dating back as far as the 1970s show that the front of the glacier has remained in the same place for decades. But in 2001 it began retreating rapidly, moving back four and a half miles between 2001 and 2005. Howat's measurements also show that the Helheim glacier has sped up from around 70 feet per day to nearly 110 feet per day and thinned by more than 130 feet since 2001.

As the glacier speeds up and retreats, new factors come into play that cause further acceleration and retreat, Howat said. "This is a very fast glacier, and it's likely to get faster," he said.

The Helheim glacier is a river of ice that pours from the inland Greenland ice sheet, through a narrow rift in the coastal mountain range, and down into the sea at a rate of several miles per year. In the sea, the glacier's weight keeps it firmly resting on the bottom, as long as the water depth is less than about nine-tenths of the glacier's thickness. Where the water is deep enough to cause the end of the glacier to float, its front becomes brittle and crumbles into icebergs, Tulaczyk explained.

Warming disrupts the delicate balance between glacier thickness and water depth by melting and thinning the glacier. If the glacier thins beyond a critical point, it becomes ungrounded, floats, and rapidly disintegrates. Temperatures in Greenland have increased by more than five degrees Fahrenheit (three degrees Celsius) over the last decade.

"Outlet glaciers may have been thinning for over a decade," Howat said. "But it’s only in the last few years that thinning reached a critical point and began drastically changing the glacier's dynamics."

The retreating front of the glacier causes it to move down the mountain slope more rapidly. This thins the glacier further, which causes upstream parts of the glacier to perceive a steeper slope and begin moving faster, Tulaczyk said.

Many fiords, the channels carved by glaciers flowing into the sea, are deep with a shallow lip in front. Once the glacier floats off this shallow pinning point, it retreats into deeper water, making further disintegration likely, Howat said.

Reduced friction between ice and rock at the glacier bed can also increase glacier speed. Fiords often widen inland, causing the glacier to grate less heavily at the fiord walls and move faster as it retreats. And ice crystals in fast-moving glaciers can realign, further reducing friction, Howat said.

The Helheim glacier's speedup has already propagated 12.5 miles up the glacier. The center of the Greenland ice sheet is only 150 miles inland, and the researchers worry that the effects of the glacier's retreat will continue to move inland, ultimately decreasing the thickness of the whole ice sheet.

"If other glaciers in Greenland are responding like Helheim, it could easily cut in half the time it will take to destroy the Greenland ice sheet," Howat said. "This is a process we thought was only happening in Antarctica, and now we're seeing that it happens really fast in Greenland."

Recent studies have shown that many other glaciers in the southern half of Greenland are retreating. To date, only one other glacier, the Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier in the southwest, has been studied sufficiently to determine that it is speeding up as it retreats. But Tulaczyk expects similar mechanisms are at work in other retreating glaciers.

"Our research provides strong evidence that rapid melting processes such as we observed at the Helheim glacier will play a role in ice sheet reduction, but they are currently not included in the models," Tulaczyk said. "My ultimate goal is to convince ice sheet modelers to incorporate this dynamic process in the models."

In addition to Howat and Tulaczyk, the authors of the paper include Ian Joughin of the University of Washington and Sivaprasad Gogineni of the University of Kansas. The research was funded by grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.

Email this story

Email this story

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version

Return to Front Page

Return to Front Page