April 25, 2005

Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter's stories

lead to new book, Translation Nation

By Jennifer McNulty

A top reporter for the Los Angeles Times, Hector Tobar

takes pride in telling the stories of people who are often overlooked

by the media.

Hector Tobar, author of Translation

Nation, is now Buenos Aires bureau chief for the Los

Angeles Times. Photo:

Jerry Bauer

|

|

One of his best days on the job was actually a night he spent

under the stars on the war-torn Iraq-Syria border.

Tobar was sent to Baghdad in June 2003 to cover the early days

of the war. In the wake of a failed U.S. attack targeting Saddam

Hussein, Tobar traveled to the remote Iraqi border village that

had been hit.

He arrived late in the afternoon. The only American in the

village, Tobar was immediately surrounded by a dozen Bedouin

children, who looked at him like he “was from outer space.”

Tobar realized there wasn’t time to do his reporting and

get back to Baghdad by curfew. He stayed to get the villagers’

story.

The hamlet was an outpost for Bedouin smugglers, the most

successful of whom lived in spacious concrete houses. Tobar

talked with residents, who spoke of a mother and infant who

were killed in the attack and five homes that had been destroyed.

Then, in a surreal twist, Tobar was invited into the home of

a local sheik, where he sat with several men and watched a televised

press conference of U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld discussing

the attack that had rocked the village hours earlier.

Tobar filed his story by satellite phone. That night, he slept

under the stars beside his translator and driver.

“I felt lucky to be a journalist that night,” says

Tobar. “It was worth the little bit of fear I felt. Looking

up at Scorpio, I had never seen its star so bright. I felt connected

to this really distant, strange, exotic place, and I had told

their story.” It ran under the headline, “Tiny Bedouin

Village Is Caught in Path of the Hunt for Hussein.”

Tobar, now Buenos Aires bureau chief for the Los Angeles

Times, has had an outstanding career, sharing the 1992 Pulitzer

Prize for the paper’s coverage of the Los Angeles riots.

“Talking to people and telling stories—it’s an

honorable living,” he says.

The son of Guatemalan immigrants, Tobar was raised in southern

California. “My mother was 19 and pregnant, and my father

had saved up enough money for a television or to move to the

United States or Europe. He decided the television could wait,

and they moved to Los Angeles.”

Tobar’s father began working in hotels and delivering

the newspaper his son would later write for. Tobar attended

public schools and got good grades, but it wasn’t until

college that his eagerness to learn was reciprocated. “In

college, I met people who really challenged me,” he says.

At UCSC, Tobar took and audited classes in everything from

biology to McCarthyism. He learned about national liberation

struggles from literature professor Roberto Crespi in the Oakes

College core course and “suddenly got the bug to learn

this history of Latin America that I had not been taught,”

he says.

Crespi, who died in 1992, was “one of the most dogmatic

people I’ve ever met. He believed in the creative process,

and he demanded it from his students,” says Tobar. Sociology

professor Jim O’Connor had “a passion for social change.

I felt lucky to be in his presence and to listen to his lectures.

I remember looking at the world differently.”

Ultimately, says Tobar, UCSC is what made him a writer. After

graduating, he started out in 1988 at a community newspaper

in San Francisco. He earned $9/hour and felt he was in heaven

because he was being paid to write. Tobar moved a year later

to the Times, where he participated in the paper’s

Minority Editorial Training Program, was hired, and spent four

years as a metro reporter. That “first incarnation”

of his career, as Tobar describes it, ended unhappily. He felt

like the paper’s “token Latino,” and he was emotionally

drained from his work on the police beat.

“One of the things that made me a good reporter was that

I had an excess of empathy,” he says. “When I was

in my mid-20s, I had a very gentle soul. I would weep with people,

and after a while, they would not be able to stop talking about

their son or daughter who had died.”

Tobar left the paper to explore fiction writing, He earned

an M.F.A. in creative writing from UC Irvine, and published

his first book, the novel The Tattooed Soldier. The experience

helped him find his “inner poet,” and he returned

to the Times in 1996. Today, he is considered one of

the paper’s best “stylists,” a distinction that

prompts a self-conscious laugh.

“The first time I was a journalist, I was cautious, having

learned that it was forgivable to be late, boring, or to write

flat prose, but that if you messed up the facts, you wouldn’t

be a journalist very long,” explains Tobar. “Fiction

let my imagination loose.”

Shortly after returning to the paper, Tobar felt the familiar

chafing of racial politics. He was the only Latino reporter

on the daily metro staff. “I’m not really big on race

or ethnicity, but I’ve never felt so brown in all my life,”

recalls Tobar.

He told his editor he was going to quit but was urged to stay

on. Weeks later, the Times announced its “Latino

Initiative,” and Tobar got “one of the best jobs in

the world.” As Latino national affairs correspondent, and

then as a roving national correspondent, Tobar had license to

go anywhere in the country. And he did.

“I had so many story ideas—story ideas are really

what’s carried me in journalism.”

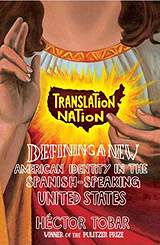

Those stories inspired his new book, Translation Nation:

Defining a New American Identity in the Spanish-speaking United

States, which arrives in stores this week. The book weaves

together Tobar’s wanderings through what he calls the new

“Latin Republic of the United States,” beginning with

his parents in Los Angeles and ending in Baghdad, where he does

a favor for a Dominican American military policeman from Brooklyn.

Tobar feels privileged to “give voice” to so many

people he’s encountered in his travels, and he is grateful

to his wife, UCSC alumna Virginia Espino (psychology, 1987),

who makes his work possible. The two met at UCSC but didn’t

connect until years later in Los Angeles. The couple have three

children—Dante, 8; Diego, 5; and Luna, 5 months.

“My wife is extremely understanding,” says Tobar,

who finished his book by rising early and writing before the

kids woke up. “It’s the ambition. My ambition is such

that it’s a disease. It’s an obsession.”

Email this story

Email this story

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version

Return to Front Page

Return to Front Page