|

June 23, 2003

UCSC scientist part of team decoding gamma-ray

burst mystery

By Christopher Watjen

Scientists have pieced together the key elements of a gamma-ray burst,

from star death to dramatic black hole birth, thanks to a March 29 explosion

considered the "Rosetta stone" of such bursts.

|

|

|

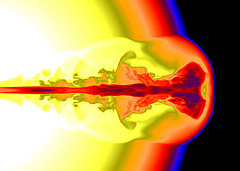

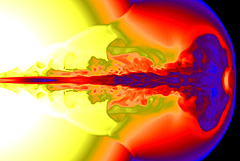

This computer simulation shows the beginning of a gamma-ray

burst. Above, the jet is shown 9 seconds after its creation at

the center of a Wolf Raye star by the newly formed, accreting

black hole within. Below, the jet is just erupting through the

surface of the Wolf Rayet star, which has a radius comparable

to that of the sun. Blue represents regions of low mass concentration,

red is denser, and yellow denser still. Note the blue and red

striations behind the head of the jet. These are bounded by internal

shocks. Images: Weiqun Zhang and Stan

Woosley

|

|

|

| Additional images and animations

are available online. |

The results are described in the June 19 issue of Nature, in

an article coauthored by Stan Woosley, professor and chair of astronomy

and astrophysics at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The telling March 29 burst in the constellation Leo, one of the brightest

and closest on record, reveals for the first time that a gamma-ray burst

and a supernova--the two most energetic explosions known in the universe--occur

essentially simultaneously, a quick and powerful one-two punch.

The burst was detected by NASA's High-Energy Transient Explorer (HETE)

and observed in detail with the European Southern Observatory's Very

Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile.

"The March 29 burst changes everything," said Woosley. "With

this missing link established, we know for certain that at least some

gamma-ray bursts are produced when black holes, or perhaps very unusual

neutron stars, are born inside massive stars. We can apply this knowledge

to other burst observations."

The research team said that just as the Rosetta stone helped us understand

an ancient language, this burst will serve as a tool to decode other

gamma-ray bursts.

Woosley and his graduate student, Weiqun Zhang, created computer simulations

of a gamma-ray burst using one of the fastest unclassified computers

in the world, at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Using 128 computer

processors simultaneously, Woosley said the simulations took about two

weeks--or about 25,000 processor hours. Woosley is director of the Center

for Supernova Research, funded by the Department of Energy's Scientific

Discovery through Advanced Computing (SciDAC) program. The other partner

institutions are the University of Arizona and the Los Alamos and Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratories.

A supernova is the explosion of a star at least eight times as massive

as the Sun.

When such stars deplete their nuclear fuel, they no longer have the

energy to support their mass. Their cores implode, forming either a

neutron star or (if there is enough mass) a black hole. The surface

layers of the star blast outward, becoming a billion times as luminous

as the Sun.

Scientists have suspected gamma-ray bursts and supernovae were related,

but they have had little observational evidence, until March 29.

"We've been waiting for this one for a long, long time,"

said Jens Hjorth, University of Copenhagen, lead author of the Nature

article, one of three related "letters" appearing in the issue.

"The March 29 burst contains all the missing information. It was

created through the core collapse of a massive star."

The research team said that the Rosetta stone burst also provides a

lower limit on how energetic gamma-ray bursts truly are and rules out

most theories concerning the origin of "long bursts," lasting

longer than two seconds.

Gamma-ray bursts temporarily outshine the entire universe in gamma-ray

light, packing the energy of over 100 million billion Suns.

"It is as bright as if two thousand Earth masses were abruptly

turned to energy in the form of gamma rays," said Woosley. "Any

life within the path of the burst inside of several hundred light-years

would have been obliterated."

Yet these explosions are fleeting--lasting only seconds to minutes--and

occur randomly from all directions in the sky, making them difficult

to study.

GRB 030329, named after its detection date, occurred relatively close,

approximately 2 billion light-years away (at redshift 0.1685). The burst

lasted over 30 seconds. ("Short bursts" are less than 2 seconds

long.) GRB 030329 is among the 0.2 percent brightest bursts ever recorded.

Its afterglow lingered for weeks in lower-energy X-ray and visible light.

With the VLT, Hjorth and his colleagues uncovered evidence in the afterglow

of a massive, rapidly expanding supernova shell, called a hypernova,

at the same position and created at the same time as the afterglow.

The following scenario emerged:

Thousands of years prior to this explosion, a very massive star, running

out of fuel, let loose much of its outer envelope, transforming itself

into a bluish Wolf-Rayet star. The Wolf-Rayet star--containing about

10 solar masses worth of helium, oxygen, and heavier elements--rapidly

depleted its fuel, triggering the Type Ic supernova/gamma-ray burst

event. The core collapsed, without the star's outer part knowing. A

black hole formed inside surrounded by a disk of accreting matter, and,

within a few seconds, launched a jet of matter away from the black hole

that ultimately made the gamma-ray burst.

The jet passed through the outer shell of the star and, in conjunction

with vigorous winds of newly forged radioactive nickel-56 blowing off

the disk inside, shattered the star. This shattering represents the

supernova event.

Meanwhile, collisions among pieces of the jet moving at different velocities,

all very close to light speed, created the gamma-ray burst. This "collapsar"

model, introduced by Woosley in 1993, best explains the observation

of GRB 030329, as opposed to the "supranova" and "merging

neutron star" models.

In previous gamma-ray bursts, scientists had found evidence of iron

in the afterglow light, a signature of a star explosion. Also, the location

of a supernova occurring in 1998, named SN1998bw, appeared to be in

the same vicinity as a gamma-ray burst. The data was inconclusive, however,

and many scientists remained skeptical of the association.

"Supernova 1998bw whetted our appetite," said coauthor Chryssa

Kouveliotou of the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville,

Alabama. "But it took five more years before we could confidently

say we found the smoking gun that nailed the association between gamma-ray

bursts and supernovae."

"This does not mean that the gamma-ray burst mystery is solved,"

Woosley said.

"We are confident that long bursts involve a core collapse, probably

creating a black hole. We have convinced most skeptics. We cannot reach

any conclusion yet, however, on what causes short gamma-ray bursts."

Short bursts might be caused by neutron star mergers. A NASA-led international

satellite named Swift, to be launched in January 2004, will "swiftly"

locate gamma-ray bursts and may capture short-burst afterglows, which

have yet to be detected.

The VLT is the world's most advanced optical telescope, comprising

four 8.2-meter reflecting Unit Telescopes and, in the future, four moving

1.8-meter Auxiliary Telescopes for interferometry. HETE was built by

MIT as a mission of opportunity under the NASA Explorer Program, with

collaboration among U.S. universities, Los Alamos National Laboratory,

and scientists and organizations in Brazil, France, India, Italy, and

Japan.

Louise Donahue contributed

to this story.

Return to Front Page

|